City Secrets : Shaft House

We pride ourselves as a local NYC brand, and are constantly inspired by its vibrant stories. Among our favorite New York urban legends is an account of the most unusual public architecture that are secretly scattered across the city.

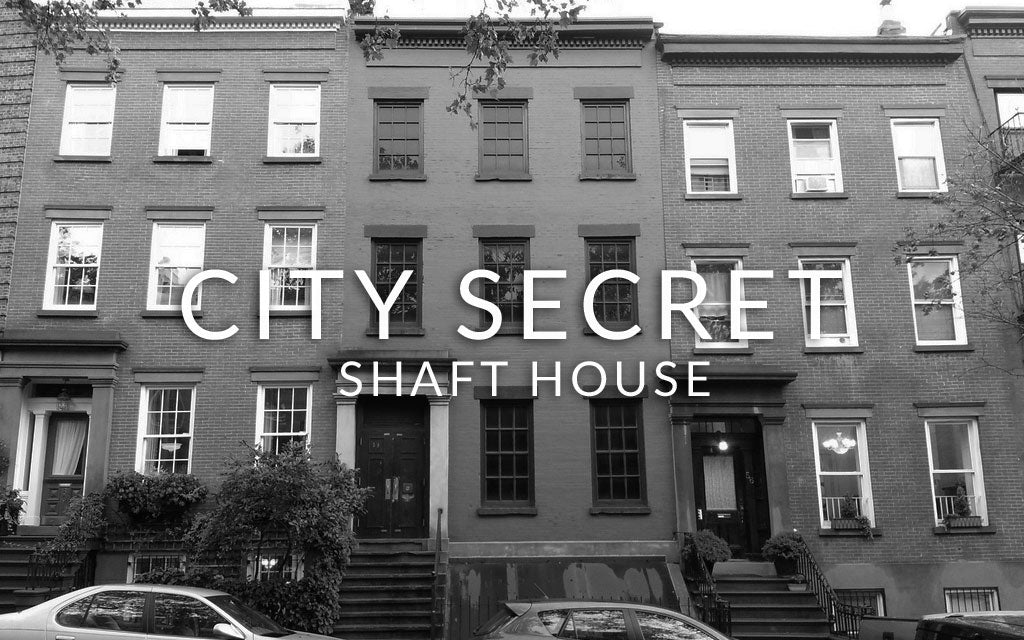

It looks just like another beautiful 19th-century Brownstone on an elegant block of Brooklyn Heights. But if you end up living next to it, you will soon realize that the building, known to its neighbors as the Shaft House, is no ordinary architecture. The windows are fitted with opaque sheets of black Lexan and remain dark from day to night, with no signs of life behind them. Odd, echoing sounds and rumbling reverberate through its walls, and hot air sometimes whooshes from the edges of its door.

“A secret military R&D base?” You may wonder.

Kept discreet for security reasons, the Shaft House is in fact an emergency exit and fan play for the NYC subway–lines 4 and 5 to be precise. Owned by the city and operated by New York City Transit and its predecessors for nearly a century, the building is installed with powerful ventilation equipment that can push in fresh air or expel smoke in a fire in the subway tunnel.

This urban oddity began in 1847 as an ordinary brick-and-brownstone Greek Revival row house, according to landmarks commission documents. When the city expanded subway service into Brooklyn in 1908, the building was converted into a fan plant, and its windows were outfitted with industrial steel shutters, whose louvers vented air from the subway tunnel below.

The Shaft House owes its present disguise to the Landmarks Preservation Commission and to a local community association, which urged that the plant's exterior be restored in an unobtrusive, historically appropriate manner during a recent renovation. Especially after the tragedy of 9/11, the city likes to keep some things discreet.

It’s not just in Brooklyn that the city keeps its secret ventilation outlets. In 2011, the MTA proposed several designs for a facade to hide a future emergency ventilation plant at Mulry Square on Seventh Avenue and Greenwich Avenue. The proposals faced vigorous opposition from community groups who deemed that a floating,”faux historic” facade was the wrong approach. The design went through many iterations since 2007, including a living wall, a concrete modern design and some bland faux brick proposals.

Elsewhere, New York’s ventilation control structures are “strange buildings” that have “collapsed” the difference between architecture and civil engineering, according to historian David Gissen. The Holland Tunnel is a good example.

At each end of the interstate tunnel, which spans over 8,500 feet, engineers designed ten-story ventilation towers that would push air through tunnels above the cars. The exhaust towers provided a strange new building type in the city—a looming blank tower that oscillated between a work of engineering and architecture.

Just like the legacy of Brooklyn Army Terminal, where we are based, New York is full of hidden tales like these that continue to live in the streets and buildings we pass by every day. We just need to pay attention to discover them as the inspiration we can receive is limitless.

Words: Aiko Austin

Resources:

http://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/26/nyregion/thecity/a-puzzle-tucked-amid-the-brownstones.html

http://www.bldgblog.com/2011/12/brooklyn-vent/